The Hungarian Kingdom

To

be formally recognized as a Christian king, one had to ask to be crowned by

either the Pope or another king, but in this case he would be accepting him as

his superior. Realizing

this, István the first Christian king of

To

be formally recognized as a Christian king, one had to ask to be crowned by

either the Pope or another king, but in this case he would be accepting him as

his superior. Realizing

this, István the first Christian king of

Exhibit 24: Saint István from the Illustrated Chronicle

The

brother-in-law of István, Emperor Heinrich

II, died in 1024 and the good relationship between

The

brother-in-law of István, Emperor Heinrich

II, died in 1024 and the good relationship between

Exhibit 25: St. István offers

István

died on

Exhibit 26:

László

was followed to the throne by King Kálmán

(1095-1116), the "Book Lover".

He was probably the most learned king of his time. He decreed: "witches do not exist", and

forbade witch hunts. He also relaxed cruel and unusual punishment for crimes

that did not warrant it. Yet, Kálmán was a firm and wise ruler. He became the

crowned King of

Taxation

and other excesses of government under the rule of King András II (1205-1235) created great dissatisfaction. The threat of

revolution loomed. Donating large portions of land to his supporters backfired

in the end as trouble continued to brew; the financially weakened King seemingly

added fuel to an already perilous fire. In order to bring about calm and order,

in 1222, András issued the Bill of

Rights. Known as the Aranybulla

(Exhibit 27) (i.e., the Golden Bull is similar to the British Magna Carta

document of 1215), the document unfortunately did not solve the problems that

existed -

András did not remove the government which was the cause of the dissatisfaction

in the first place.

Taxation

and other excesses of government under the rule of King András II (1205-1235) created great dissatisfaction. The threat of

revolution loomed. Donating large portions of land to his supporters backfired

in the end as trouble continued to brew; the financially weakened King seemingly

added fuel to an already perilous fire. In order to bring about calm and order,

in 1222, András issued the Bill of

Rights. Known as the Aranybulla

(Exhibit 27) (i.e., the Golden Bull is similar to the British Magna Carta

document of 1215), the document unfortunately did not solve the problems that

existed -

András did not remove the government which was the cause of the dissatisfaction

in the first place.

Exhibit 27: Boundary stone of Babylon and the seal of King András II.

The Sun, the Moon and the rosette are displayed on both objects

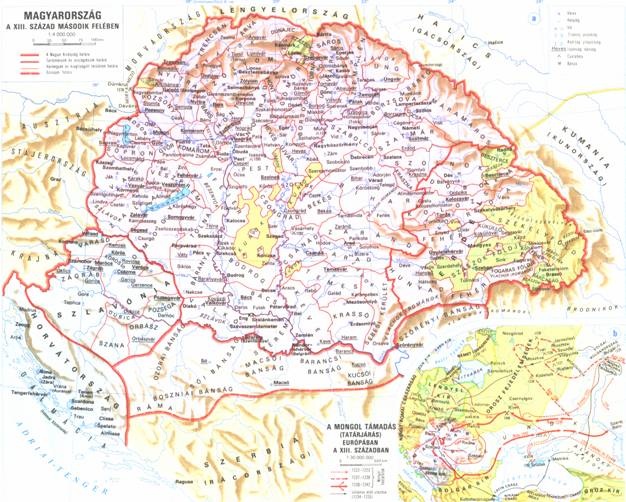

After

the death of András, his son inherited the throne as King Béla IV (1235-1270). His aim was to create a stable and powerful

government and bring about respect for the throne. In order to do this, he took

back the lands that had been given away by his father, levied new taxes, and

made friends with no one. Obviously, dissatisfaction became rampant throughout

the country. At this time, in 1241, news came that the Mongolian Armies of Batu Khan were approaching Hungary. A

large number of Kuns (Kumanians) along with their king, Kutten, fleeing from the advancing Mongolian Armies, were given

permission to settle in Hungary. Béla hoped that they would be of great help in

the upcoming struggle. King Béla called the country to arms, but the enraged and uncooperative aristocracy either did not

respond or came up with conditions. One of their demands was that the King turn

over Kutten to the Mongols. Batu sent his envoys to Béla with the same demand.

The King's enemies murdered the envoys - an unforgivable crime. They

also murdered Kutten, resulting in his warriors turning on the Hungarians in

revenge; consequently most of them fled the country. Béla suffered a crushing

defeat from the Mongolians at Muhi (eastern Hungary), barely escaping capture;

meanwhile, Béla's wife and the King's treasury fell into the hands of Prince Friedrich II of Austria. In order to

regain the freedom of his wife, the treasury had to be forfeited, along with

claims to three western counties while Friedrich joined the Mongols to loot and

rampage. The Mongols were cruel and merciless, not surprisingly, avenging their

murdered envoys. From Zagreb, the fleeing King Béla turned to the Pope, the

French king, and the German emperor for help; his requests were turned down. In

the spring of 1442, the Mongols left Hungary and the King returned to begin the

rebuilding of the country.

The

last male in the direct heir of the

Árpád Dynasty, King András III died

in 1301. The grandchild of the daughter of King István V, Robert Károly,

was elected to the throne in 1308. Robert Károly was to become one of the

greatest kings of Hungary. His wise economic and foreign policy made the

country rich again and regained its old glory and respect. His son, Lajos "The Great" (1342-1382),

inherited a rich and powerful country. Lajos was a peaceful and courageous man,

but he did not have his father's leadership qualities. His restless and

ego-driven mother was the force behind many of his decisions. They emptied the

coffers of the treasury to wage war and bribed people to further their goals.

Lajos expanded the borders of his kingdom to the furthest that they would ever

reach (this is why "The Great" was bestowed upon him) and in the

process bankrupted the country yet

again. In the meantime, Turkish armies were approaching from the south reaching

the borders of the Hungarian Kingdom in 1373.

After

the death of Lajos, Hungary fell into feudal anarchy. Rich and powerful members

of the aristocracy quarreled amongst themselves and ruined the country. They

elected weak kings in order that the kings would serve them. Out of this chaos,

the figure of a great military leader, János Hunyadi, emerged as the savior of the country. The decadent

aristocracy did not dare to confront him, so in 1446 he was elected to be the

Governor of Hungary, with most of the king's authority delegated to him. He

resigned this post in 1452, so he could take firm control of the military. King

László V appointed him to be General

of the Armies and he became the caretaker of the King's treasury as well.

In

June of 1456 the Turkish sultan, Mohammed

II, marched his armies to capture Nándorfehérvár (today's Belgrade) on his

way to conquer Europe. With a massive army of some 150,000 foot soldiers, 300

cannons, and 200 ships, the city was encircled. The defenders, under the

leadership of Mihály Szilágyi (the

brother-in-law of Hunyadi), numbered only around 6,000. With the help of some

12,000 men, János Hunyadi and John Capistrano

(a Franciscan monk) broke through the encirclement and established contact with

the defenders as more supplies and an additional 2,000 reinforcements were sent

in. The Pope ordered prayers and church bells to ring at noon for victory. By

this time, Hunyadi's forces in and outside of the city numbered about 25,000

strong. The Turks launched their final attack on the 21st of July.

Hunyadi, Szilágyi and Capistrano were able to beat back the Turks, launching a

counterattack and destroying the Turkish forces the very next day. The ringing of the church bell at noon is

still a reminder of this victory. With this victory, Europe was saved from

Turkish invasion; however, a plague broke out as a result of the decomposing

bodies in the great summer heat. In three weeks, Hunyadi fell victim to the

plague. Kings, leaders, and soldiers of Europe paid tribute to Hunyadi; even

Muhammed II sent his condolences remarking, "The

world has never seen such a man". About two months later, Capistrano

also fell victim to the plague. He became a saint of the Roman Catholic Church;

in California, Capistrano Beach is named after him.

The

enemies of the Hunyadis, under the leadership of Cillei and Garai, used

this opportunity to capture Hunyadi's sons, László

and Mátyás. They beheaded László and

kept Mátyás in captivity. The weak King László

V., fearing for his life, escaped to Vienna (and then to Prague) taking

Mátyás with him as a hostage. The friends of the Hunyadis took great exception

to this, and Szilágyi paid 40,000 pieces of gold in ransom to gain his release.

Mátyás

(Exhibit 28) was elected to the throne in 1458 and became one of Hungary's

wisest, most powerful, and most beloved rulers. Mátyás enacted laws which were

evenhanded and just. There are numerous legends surrounding him; there is even

a saying often repeated today: "Mátyás

the Just died - and so did justice." He

set up a well-trained Black Army (a

mercenary force whose uniforms were black) for the defense of the country. His

campaign against the Turks was as successful as his father's had been. However,

more than once, he had to buy peace from the Turks in order to defend the

country from the West and keep the internal enemies in check. Mátyás was one of

the most learned rulers of his time - his library was famous

throughout Europe. He ran a splendid court which was the envy of Europe visited

by scholars and scientists from all over the continent. He died - probably at

the hands of an assassin - at the age of 50, in 1490. He was the last great and

powerful King of Hungary. The anarchy among the aristocracy now re-emerged,

worsening the internal conditions to the point that in 1541 the Turks marched

into Buda and took over the city without any resistance.

Mátyás

(Exhibit 28) was elected to the throne in 1458 and became one of Hungary's

wisest, most powerful, and most beloved rulers. Mátyás enacted laws which were

evenhanded and just. There are numerous legends surrounding him; there is even

a saying often repeated today: "Mátyás

the Just died - and so did justice." He

set up a well-trained Black Army (a

mercenary force whose uniforms were black) for the defense of the country. His

campaign against the Turks was as successful as his father's had been. However,

more than once, he had to buy peace from the Turks in order to defend the

country from the West and keep the internal enemies in check. Mátyás was one of

the most learned rulers of his time - his library was famous

throughout Europe. He ran a splendid court which was the envy of Europe visited

by scholars and scientists from all over the continent. He died - probably at

the hands of an assassin - at the age of 50, in 1490. He was the last great and

powerful King of Hungary. The anarchy among the aristocracy now re-emerged,

worsening the internal conditions to the point that in 1541 the Turks marched

into Buda and took over the city without any resistance.

Exhibit 28: King Mátyás from the Illustrated Turóczy Chronicle

The

explanation that the demise of the powerful Hungarian Kingdom had resulted from

the defeat at the hands of the Turks in 1526 at Mohács is inaccurate. That

battle took place on August 29, 1526, King Lajos

II losing his life also. The victorious Turkish troops wandered all over

the country to loot and pillage. They stumbled into heavy local resistance and

by mid-October had left the country; the Turks did not keep Hungary under

occupation, much as the Soviet had in 1945.

It

can be stated, unequivocally, that the demise of Hungary's greatness was caused

by the decadence of the Hungarian aristocracy. In fairness, the point must be

made that decadence is not unique to the Hungarian aristocracy. It is the

result of material riches and feeble human character, demonstrable in the

history of any nation or country. In the case of Hungary, it became disastrous;

during this time of grave external danger no ironhanded leaders emerged (such

as the Hunyadis had earlier) to save and protect the country. Hungary at that

time had the economic and military power to stand up to the Turks -

especially, if she did not have to defend herself from the Western threats at

the same time. Hungary has an important geographic location, dividing Europe

into the western and eastern civilizations. Culturally, Hungary had broken away

from the East half a millennium

earlier, yet was never fully accepted by the West. In her struggle for

survival, Hungary defended not only herself from eastern invasions, but also

defended the West. The West watched this struggle indifferently, at times

seizing the opportunity and launching an attack on her.

The

following is an excellent case in point, an illustration as to what it takes to

destroy a nation or a great power -- any nation or any great power. After the

tragic battle at Mohács, on the 10th of November, a group of

aristocrats gathered at Székesfehérvár and elected János Szapolyai (1526-1540) to the throne. The aristocrats opposing

Szapolyai gathered at Pozsony on the 16th of December electing the

Habsburg Prince Ferdinand (1526-1564) to be King. (This event laid the foundation

of the Austrian-Hungarian Monarchy, the Habsburgs keeping the Hungarian crown

for the next 400 years.) The primary goal of these two kings for the next

thirteen years was to gain the upper hand or, if possible, destroy the other.

In this struggle, Szapolyai more than once acquired the help of the Turkish

sultan, Suleiman II. Ferdinand, of

course, received help from Austria and from the West. In 1538, they finally

made peace. Szapolyai agreed that after his death Ferdinand should become the

sole king. Just as had happened with Emperor Manuel many years earlier, a son

was born to Szapolyai two weeks before his death and he ordered his followers

to elect the baby to be the new king. Suleiman was made guardian of the Baby King. On August 29, 1541, on the

very day of the 15th anniversary of Mohács, Suleiman marched into

Buda under the pretense of protecting the interest of the Baby King, and

stayed.

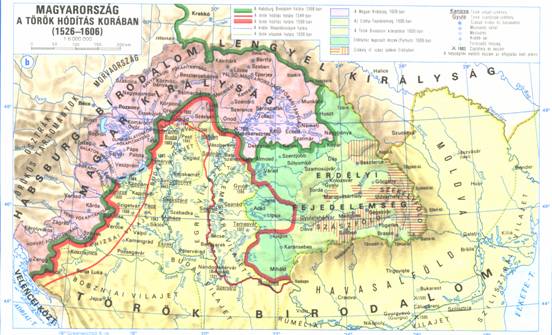

Exhibit 29: The Turkish conquest and occupation

(yellow wedge)

The

advancing Turkish armies occupied the Great Plains and most of Dunántúl

(western Hungary). Transylvania had purchased peace from the Sultan, thereby

enabling it to keep its internal "independence". A narrow strip of

western Hungary, along with the northern Carpathians, remained under Hungarian,

that is, Habsburg rule. The following 150 years were to be an era of valiant

struggle to free the country from Turkish occupation and Habsburg domination.

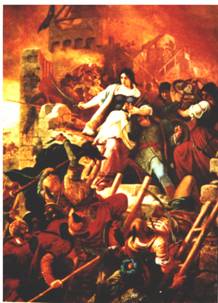

We can take the heroines of Eger or the defenders of Szigetvár as examples of this

great effort. In 1552, the women of Eger (Exhibit 30) fought alongside their men

against  overwhelming

odds. Some fought with swords in their hands; others threw rocks or dumped

boiling water on the invaders. Their efforts led to an incredible victory over

the besieging Turks.

overwhelming

odds. Some fought with swords in their hands; others threw rocks or dumped

boiling water on the invaders. Their efforts led to an incredible victory over

the besieging Turks.

Exhibit 30: The heroines of Eger by Bertalan Székely

Sadly,

the heroes of Szigetvár weren't quite so lucky. In 1566, some 2,500 Hungarians

and Croatians defended their city surrounded by some 90,000 Turks. In attack

after attack, they repelled the Turkish charges, inflicting heavy casualties

upon them. Some 25,000 Turks died at Szigetvár, but because of their large

numbers, they persisted in their

attack on the city. With the number of defenders dwindling to about three

hundred, their supplies having been used up; further resistance looked

hopeless. The wives and daughters of the officers decided that they would

rather die than fall into Turkish hands as well as dragged into slavery. They

were killed by their husbands and fathers before the final counterattack. Count

Miklós Zrinyi gathered his loyal

troops and led the last brave and furious charge; all but three of them died

heroes' deaths.

Exhibit 31: Mihály Dobozi and His Wife by Bertalan Székly

Though

encircled, Transylvania enjoyed internal stability. History was made in 1568

when the Diet (Congress) of Torda declared religious freedom there, giving each individual the right to

choose his or her own religion - further proving that Hungary was at the forefront of social development

in Europe. At the very least, part of the country was able to exercise its

domestic freedom. The Turks were forced out of Hungary in 1699; only five years

later the anti-Hungarian policy carried out by the Habsburgs resulted in a War

of Independence led by Count Ferenc Rákóczi II.

After the Turks had been expelled, the

Hungarians moved back to reclaim their former properties. The Habsburg armies

chased them off and brought in foreign settlers to take their place. This became the basis for the Treaty of Versailles (Trianon) in 1920. It would be unfair to say that the Habsburgs alone

were responsible for the dismemberment of Hungary, as the Hungarian nobility

had done more than its share in this regard. In Transylvania, they brought in

large numbers of Rumanians for cheap labor. The grandfather of Rákóczi II,

György Rákóczi, translated the Bible into Rumanian, so they could be educated

and cultured, and of course the pay-off came in the first quarter of the XX

century. It is ironic that after the War of Independence was lost in 1711,

Rákóczi escaped to Turkey where he died and was buried. One of his military

leaders, Count Miklós Bercsényi,

went to France and organized the French cavalry into an effective fighting

force. Out of this unit came Colonel Mihály Kováts

(Exhibit 32), who did the same to the American cavalry. He died at Charleston

in the American War of Independence in

1779, leading the cavalry charge

against the British. Interestingly enough, another Hungarian cavalryman,

Captain Károly Zágonyi, fought and

led the first victorious battle on the Union side of the American Civil War at

Springfield, Missouri in 1861.

Exhibit

32: Colonel Mihály Kováts by Zoltán de Bényey

The

Turkish conquest and Habsburg domination could not have come at a worse time in

Hungarian history. The Renaissance renewed and revitalized European cultural

and spiritual life. Universities and colleges had been built throughout Europe,

while Hungary in the XV and XVI centuries spent her economic fortune on defense

against the Turks. Afterward came 150 years of Turkish occupation resulting in

one third of the country being ravaged and depopulated. As devastating as the Turkish occupation and Habsburg domination was

with its resulting internal strife and discord, these were not the only reasons

that Hungary could not regain her

independence. In the early or mid-1700's, a new social order was in the

making all across Europe. Beginning first in France in 1789, this new order

became the guiding force in social and national life as it swept away the old.

In the old order, the guiding force was loyalty to the ruler. In the new social

order, the nation was elevated to an

idealistic high. In

light of this new patriotic ideal, the western nations rewrote their history

books in service to the nation, and this ideal became the dominant force

guiding their society. Relentlessly and mercilessly it rolled over

ethnic groups like a steamroller and, in the West, most minorities disappeared

overnight. In Hungary, had this new nationalistic idea

taken root, social order could have grown as a result of the sound economic

policies of Count István Szécheny (Exhibit

33). But the War for National Independence of 1848-49,

led by Lajos Kossuth, was put down

and with it all social and economic advancement went up in flames. Therefore, a

true national identity never had the chance to take hold in the minds and

hearts of Hungarians as a firm social guiding force. Hungary at the time of the

birth of this new national consciousness was under foreign domination and still is to this very day. As a

result, Hungarians never had an opportunity to write their own history in the

best interest of their very own nation. It is in

this written history in which the information is accumulated that is necessary

to build national self-respect and a sound future. If the written history is

negative and demeaning, it will destroy the spirit of a nation. Any nation.

The

Turkish conquest and Habsburg domination could not have come at a worse time in

Hungarian history. The Renaissance renewed and revitalized European cultural

and spiritual life. Universities and colleges had been built throughout Europe,

while Hungary in the XV and XVI centuries spent her economic fortune on defense

against the Turks. Afterward came 150 years of Turkish occupation resulting in

one third of the country being ravaged and depopulated. As devastating as the Turkish occupation and Habsburg domination was

with its resulting internal strife and discord, these were not the only reasons

that Hungary could not regain her

independence. In the early or mid-1700's, a new social order was in the

making all across Europe. Beginning first in France in 1789, this new order

became the guiding force in social and national life as it swept away the old.

In the old order, the guiding force was loyalty to the ruler. In the new social

order, the nation was elevated to an

idealistic high. In

light of this new patriotic ideal, the western nations rewrote their history

books in service to the nation, and this ideal became the dominant force

guiding their society. Relentlessly and mercilessly it rolled over

ethnic groups like a steamroller and, in the West, most minorities disappeared

overnight. In Hungary, had this new nationalistic idea

taken root, social order could have grown as a result of the sound economic

policies of Count István Szécheny (Exhibit

33). But the War for National Independence of 1848-49,

led by Lajos Kossuth, was put down

and with it all social and economic advancement went up in flames. Therefore, a

true national identity never had the chance to take hold in the minds and

hearts of Hungarians as a firm social guiding force. Hungary at the time of the

birth of this new national consciousness was under foreign domination and still is to this very day. As a

result, Hungarians never had an opportunity to write their own history in the

best interest of their very own nation. It is in

this written history in which the information is accumulated that is necessary

to build national self-respect and a sound future. If the written history is

negative and demeaning, it will destroy the spirit of a nation. Any nation.

Exhibit 33: Count István Széchenyi

One

of the major problems Europe faced in the early 19th century was the

question of equal taxation. The aristocracy paid no taxes (or very little) and because of this, a heavy burden was placed on

the people of the lower echelon as well as on the serfs. It created an internal

unrest and revolution was in the making. Western countries encountered similar

situations. In early 1848, revolution broke out in Paris; Vienna shortly

followed its lead. Hungary was also ready for a revolution. The aristocracy was

certainly under great social pressure, but nonetheless, on the morning on March

15, 1848 the Hungarian aristocracy became the only upper class in history to

give up its privileges of its own free will. With this step they averted

revolution and allowed the country to turn its attention and resources to the

War of Independence. The war was going well for the Hungarians, but when the

Habsburgs were able to reach an agreement with the Russian czar in 1849

(sending some 200 thousand fresh eastern troops to the battlefields) the

outcome was determined. The war was lost and was followed by the terror of the

Bach-regime from Vienna. Hundreds of military leaders and politicians were

jailed and many were executed.

In

1867, an agreement was signed between the Habsburgs and Hungary that was to

return the country to internal independence. During and after the War of

Independence, an oligarchy seized most of the economic wealth of the country;

working from behind the scenes, it applied heavy pressure on the government,

preventing it from solving the deep rooted national problems.

The

First World War broke out in 1914 and was blamed on Hungary. This was a

malicious fabrication. One has to know that Hungary at this time was part of

the Austrian-Hungarian Monarchy, and had no foreign policy of her own. The

Prime Minister, Count István Tisza,

was the only Hungarian member of the Monarchy's government - and

he was the only one to oppose declaring war on the Serbs after the

assassination of Archduke Ferdinand at

Sarajevo. The war ended in 1918 in armistice, which was signed between Italy

and the Austrian-Hungarian Monarchy on the 3rd of November. Up until

that day not a single enemy soldier set foot on Hungarian soil; however, the

French did not recognize the armistice just signed, and kept moving their army

toward Hungary, encouraging the Czechs, the Romanians and the Serbs to do the

same. Anti-Hungarian elements seized the government, which called upon the

Hungarian troops to lay down their arms wherever they were. Most of the

Hungarian army disbanded and the remaining ones were totally

disorganized. Hungary was on the losing side and became occupied by enemy

armies.

The

First World War broke out in 1914 and was blamed on Hungary. This was a

malicious fabrication. One has to know that Hungary at this time was part of

the Austrian-Hungarian Monarchy, and had no foreign policy of her own. The

Prime Minister, Count István Tisza,

was the only Hungarian member of the Monarchy's government - and

he was the only one to oppose declaring war on the Serbs after the

assassination of Archduke Ferdinand at

Sarajevo. The war ended in 1918 in armistice, which was signed between Italy

and the Austrian-Hungarian Monarchy on the 3rd of November. Up until

that day not a single enemy soldier set foot on Hungarian soil; however, the

French did not recognize the armistice just signed, and kept moving their army

toward Hungary, encouraging the Czechs, the Romanians and the Serbs to do the

same. Anti-Hungarian elements seized the government, which called upon the

Hungarian troops to lay down their arms wherever they were. Most of the

Hungarian army disbanded and the remaining ones were totally

disorganized. Hungary was on the losing side and became occupied by enemy

armies.

Exhibit 34: The dismembered Hungarian Kingdom

In

1920 the "Peace" Treaty of

Versailles (Known to Hungarians as the Treaty of Trianon) was forced upon Hungary. As a result, historical Hungary

was dismembered (Exhibit 34). The Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and the Habsburg

Dynasty were also disbanded. This was done in the "noble" cause of "self-determination".

The newly drawn borders placed 3.5 million Hungarians under foreign rule

overnight. Of that number, 1.5 million resided along the new borders. In these

areas, the population was almost 100% Hungarian. There were 2 million

Hungarians in the expanded Rumania, 1 million in the newly created

Czechoslovakia and ˝ million in the also newly created Yugoslavia, amongst

other nationalities. Therefore, Rumania and the newly created countries were

just as diverse ethnically as Historic Hungary was. According to the

"Peace" Treaty of Trianon, the affected people should have decided by

referendum which country they wanted to belong to. This was done in only one

such case: that of Sopron, the westernmost city in modern-day Hungary.

Originally, Sopron and its vicinity had been given to Austria, but the people

voted to remain with Hungary. Because of this result, no other village or city

was given the chance for self-determination. So much for the high-sounding

principles and noble causes put forth by the "Peace" Treaty.

Exhibit 35: Ethnic divisions of the Kingdom of Hungary based on the 1910

census

This

catastrophe shocked the nation to the depths of her soul. A vibrant spiritual

and cultural renewal began to grow out of the ashes. Hungary wanted to live

again. In the late 1930's and the early 1940's, Hungary regained some of her

lost territories. This Renaissance, however, didn't last long. It was buried by

the Second World War. The war was followed by Soviet occupation and Communist dictatorship. In the second "Peace" Treaty of 1947, this

time in Paris, Hungary lost the regained territories and three Hungarian villages

on the right bank of the Danube; Slovaks wanted a foothold by the city of

Pozsony (Bratislava). The nation rose once more in 1956 (Exhibit 36), but it

was brutally suppressed. Some 200 thousand Hungarians escaped to the west, tens

of thousands were deported to the Soviet Union, and thousands were jailed and

executed in Hungary. The Communist government introduced free abortion and, as

a result, the Hungarian population began to decline in the early 1980's.

This

catastrophe shocked the nation to the depths of her soul. A vibrant spiritual

and cultural renewal began to grow out of the ashes. Hungary wanted to live

again. In the late 1930's and the early 1940's, Hungary regained some of her

lost territories. This Renaissance, however, didn't last long. It was buried by

the Second World War. The war was followed by Soviet occupation and Communist dictatorship. In the second "Peace" Treaty of 1947, this

time in Paris, Hungary lost the regained territories and three Hungarian villages

on the right bank of the Danube; Slovaks wanted a foothold by the city of

Pozsony (Bratislava). The nation rose once more in 1956 (Exhibit 36), but it

was brutally suppressed. Some 200 thousand Hungarians escaped to the west, tens

of thousands were deported to the Soviet Union, and thousands were jailed and

executed in Hungary. The Communist government introduced free abortion and, as

a result, the Hungarian population began to decline in the early 1980's.

Exhibit 36: Destruction in Budapest

It

can be safely stated that Hungary, and the Hungarian people themselves, have

never been in such grave danger in their vast history as they are today. No matter how devastating were the conditions of

the past, the birth rate had never dropped under the replacement rate; the

people and the country survived. Unfortunately, more than forty years of

Communist rule extinguished the last glimmering flame of national self-respect.

Astonishingly, perhaps all has not been lost; twelve years after the demise of

communism, some awakening can be seen in the faces of the youth of this great

and ancient nation, Hungary.